A guest post by LH Member, Richard Shearman. Part 1 of this article, published in Members Newsletter of September 2020, can be found on this blog here.

Henry Rose’s buildings of 1829-1835, together with the court in front of them and the two lodges added in 1839, filled the front part of the Asylum’s site. There was still substantial space left behind and around them for further building, and the perimeter of the site was lined with a series of residential buildings between 1848 and 1866. First came the Ladies’ Wing, completed in 1849 and so-called because of the fund-raising efforts of a group of women led by Mrs Turner, whose husband Augustus had been a Trustee (they ran the Duke of Wellington pub on Newington Causeway). Next came the Albert Wing on the southern edge of the site, the foundation stone of which was laid by the eponymous Prince in 1858. Extra houses were built to extend both these new wings, effectively making the land behind the original front ranges into an enclosed, but spacious court. Finally, in 1866 the Smalley Wing was built to the north (Old Kent Road) side of Rose’s original building. This was funded by a gift of 1000 guineas from W H Smalley, the secretary of the Society of Licensed Victuallers.

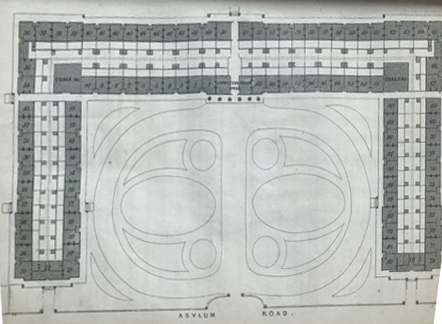

Plan of the Asylum when Henry Rose’s original buildings were complete.

The most notable building from this period however was the chapel. Some governors had ambitions to build a church within the grounds, but after objections to this from local clergy, Henry Rose was asked to design a chapel for inmates. It was an oddity of the original main buildings that the central portico fronted a void. Rose planned his chapel to be built immediately behind this portico, filling the space between his two concentric ranges. The cupola would be remodelled and bells and an external clock installed. A detached house would also be erected for the resident chaplain and his family. The project was carried out between 1850 and 1852, but at a significantly higher cost than had been agreed, largely because of the installation of gas lighting. A report by an independent surveyor largely absolved Rose from blame, but his relationship with the governors had broken down completely and in what seems like a fit of pique they ordered the deletion of all references to him in the books or on the walls of the asylum as the architect.

Despite this, the chapel was judged a success and steadily beautified during the ensuing decades, through the addition of a number of memorial plaques, and a set of stained glass windows from the well-known firm of Lavers and Barraud which were paid for by individual donors, one of whom was George Speedy, the proprietor of the Metropolitan Music Hall in Edgware Road. Under the chaplaincy of Reverend William Martin, it attracted much local support, especially for its musical activities. In 1867 Mr Martin had to cope with accusations that he had been leaning to “ritualistic” practices (Victorian England’s equivalent of “Reds under the bed”), but these blew over and his ministry won high praise . When he died in 1892 he was succeeded by Reverend William Casely, but this appointment did not turn out well. In 1898 Casely was accused of taking services when drunk, and other examples of slovenly practice. The matter was patched up after he wrote a long and lachrymose letter of apology, but trust was eroded and he left the Asylum at the end of 1901. The Vicar of nearby Christ Church in the Old Kent Road, whose vicarage was almost next door to the asylum, took on the role as a stopgap, and this became permanent after 1903 when the governors decided a resident chaplain was not necessary. The chaplain’s house was demolished and a further six houses for inmates built on its site, bringing the institution up to its final tally of 176 residences. The chapel remained a major feature of the asylum, and the Metropolitan Borough of Camberwell used it on occasion for civic services (including the ceremony to dedicate a new borough mace in 1917, captured in a short film). Despite bomb damage in 1941, the interior remains impressive today.

Houses built to replace the chaplain’s house. Image: Richard Shearman.

The chapel, 2020. Image: Richard Shearman.

The control of costs mattered because the asylum lived on a hand to mouth basis. It had no assets except the buildings and the ground they stood on, nor any large endowments or reserves. Annual subscriptions from individual Licensed Victuallers were never sufficient to meet the running costs and to build up funds, especially as the governors had decided as early as 1835 that simply providing accommodation was not sufficient and that inmates should be paid a weekly allowance, to ensure a guaranteed minimum income, as well as being provided with coals and if necessary additional funds for nursing. Fundraising was therefore a constant preoccupation and took a variety of forms. The grounds offered a good setting for bazaars and fancy fairs, and these were held from the 1830s onwards. From the 1870s, an Annual Ball was held, usually at a West End venue such as the Portman Rooms. The greatest opportunities were offered by Anniversary Dinners and Festivals, at which a leading brewer or distiller would preside (his firm would be expected to make a significant donation). Initially these dinners were held at inns such as the London Tavern in Bishopsgate, but in time other venues were used, especially the Crystal Palace at Sydenham (a grimly amusing note is struck by a letter of 1867 from the latter’s directors, reprimanding the governors for allowing smoking inside the building and stressing the dangers of this!). On significant anniversaries the current patron or another member of the royal family would preside. Although they were not expected to donate significantly, their presence usually led to greater donations from others. Even in a non-royal year such as 1892, the appeal at the anniversary celebrations could raise over £9000 – in contrast, as several newspapers pointed out, with an appeal by the Bishop of London for funds to support decayed clergymen, which raised £900!

Among other fundraising events, a cricket match at the Oval in 1902 between two teams raised by the distiller Sir Walter Dewar and the music-hall star Dan Leno stands out.

The Bowling Green.

The reliance on industry donations linked the asylum’s fortunes to those of the trade. The growth of the temperance movement from 1840 onwards, and the support given to it by some sections of the Liberal party, drew the trade into the political arena, although this never affected the Asylum’s day-to-day operations. Before the Prince of Wales presided over the 50th anniversary dinner in 1877 he received many representations that he should not patronise such a dubious trade (the former Foreign Secretary Lord Granville, who also attended, elegantly remarked that as a student of human nature, he could not pass up the opportunity to observe so many monsters of iniquity gathered together for purposes of charity and benevolence).

However, finances were a problem in the first decade of the twentieth century and there were several years in which expenditure exceeded income. There were indications that the asylum might come lower in brewers’ priorities than before; interestingly, the very name was mentioned as a potential issue. Through cost-cutting and an effort to find new sponsors, the situation was retrieved. A significant contribution was made by Mr Mazzuchi, the London representative of Mumm and Co, who presided over the 1907 dinner, and also arranged for some trustees to visit the firm’s premises in Reims. Throughout the Great War, the finances remained precariously in balance. In 1919 the Prince of Wales presided at the Anniversary Festival, handing the governors a new Royal Charter changing the name to Licensed Victuallers’ Benevolent Institution. The hugely successful events raised £28,919, and financial security was assured. The finances also benefited from the introduction of Old Age Pensions, which reduced the need to pay allowances to many of the inmates, and allowed the Institution to reduce the out-payments to approved applicants for election who had not yet been successful in the annual ballots. These payments had been introduced in 1891, but had become a significant burden.

In many ways the Institution carried on in much the same way as ever between the wars. There was no shortage of applicants for residence or of landlords coming forward to play a part in the running of it. Running a pub proved to be just as precarious an occupation for many as it always had been, and sometimes former governors found themselves petitioning for a home. Royal connections continued to be fostered; in 1935 George V, who as Patron had 10 votes in the election of new residents, sent back his ballot papers which he had completed and signed. He had cast them all for a Mr and Mrs Vincent, who fortunately were successful. The same range of activities continued to be offered to residents – as well as the amenities of the grounds, there was a library, musical events, and occasional trips to the theatre or cinema. In 1919 it was noted in the Annual Report that there had been an outing to East Grinstead in a motor charabanc.

However, there was also a sense that the institution was a Victorian one operating in a more modern era. By 1936 if not earlier, some governors and trustees were considering the future. There was no room on the site to house more residents without ruining the particular charm of the grounds, and the owners of adjoining sites did not wish to sell. The accommodation was old-fashioned. By 1939 the governors had established a committee including several past chairmen to consider the future. In 1940 the critical events of the war caused it to be adjourned until 1943, a time when many organisations were engaged in similar exercises. In the meantime the institution had suffered two bombs falling on it. The first fell in the rear grounds and only caused blast damage. The second in March 1941 was an incendiary which destroyed the roof of the chapel and much of its interior plasterwork.

In 1944 the committee reported. It concluded that the present buildings were out of date, and impractical to adapt to modern needs. The only practical rebuilding on the Asylum Road site would be as flats, which would not be acceptable. Replacing almshouses by out-pensions would be equally undesirable, because despite the recommendations of the Beveridge Report, expert advice was that institutions would still be needed. A new site was therefore needed outside London and a suitable site had been identified at Denham on which up to 250 bungalows could be built. Purchase and development of this site was agreed on 8 September 1944, and site purchase completed soon afterwards.

But shortages of labour and materials impeded the move for some years, and it was December 1958 when the buildings at “Denham Garden Village” were opened (by the Queen Mother, naturally enough). In April 1960 the Asylum Road buildings were sold to the Metropolitan Borough of Camberwell, which renamed them Caroline Gardens, apparently after Caroline Secker, an inmate in the 1840s. It ran them as sheltered housing for the elderly and its successor the London Borough of Southwark owns and manages them to this day, although not exclusively for the elderly.

There is much more to be written about the Asylum, especially about the lives of the men and women who lived there, and the licensees who ran it. It is a notable example of a trade looking to support its own members, both before and after the State concerned itself with such matters.